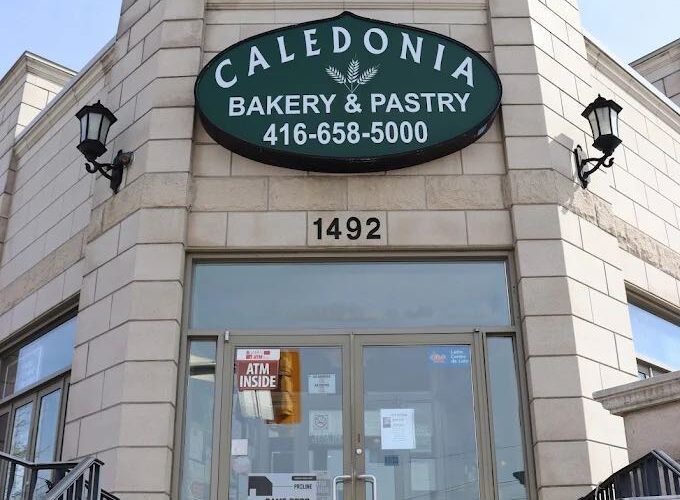

Everybody knows Caledonia Bakery. It’s a local cafe where people stop in for a tosta mista and a galao. It’s European but not fancy. You can walk in with a fluorescent vest, paint on your hands, or a friend you haven’t seen in years.

There’s always people inside but you can always find a table. It fits at the corner of St. Clair and Caledonia — not because some head office engineered it to — but because it came from the neighbourhood. Portuguese neighbours, to be exact. And now it’s slated to go.

The corner is up for redevelopment. An 18-storey condo building might be replacing the cafe, its parking lot and the car wash. But it’s not locals who want to get rid of it.

Toronto is growing. Housing costs have soared, rental demand is high, and neighbourhoods across the West End feel the pressure of a city that doesn’t have enough places for people to live. New homes are essential. More rentals are essential. More affordability is essential. Pretty much everybody agrees. We can’t afford to stand still while our population goes up. We all know that.

What residents are struggling with is not growth but with how that growth is happening. At Dufferin and Eglinton, a major development appeared with little early consultation, and residents responded with a petition against it. Soon after, another petition emerged at St. Clair West and Dufferin, where a separate project had followed the same pattern: a neighbourhood shown plans already finalized.

In the West End, development seems to happen to us, rather than for us.

That’s why Caledonia Bakery sticks out. It’s not just about a beloved local shop; it’s about development, meant to solve today’s housing crisis, that might be erasing the very places that make communities feel like home.

If a cafe that’s full every day, that belongs to the area and reflects its identity, can disappear overnight without genuine neighbourhood input, then what else can vanish under the banner of progress?

The debate isn’t about resisting development—it’s about demanding development that reflects real people, real histories, and real belonging. If Toronto gets this right, it can build a future that includes everyone. If it doesn’t, it risks becoming a place where long-time residents no longer recognize the city rising around them—or worse, no longer feel they have a place in it.

The question is, if residents aren’t included when their neighbourhood is being reshaped, who exactly is the new city being built for?